One million words: a tech-enabled review of 15 years of journaling

Understanding both the power of compound interest and the difficulty of getting it is the heart and soul of understanding a lot of things.

Charlie Munger

Introduction

One day, back in 2009, I decided to start a typed journal. I called it "the one sentence journal." The idea was that I would write at least one sentence per day for as long as possible. I had a hand-written journal for a few years prior, but because I was always in front of a computer, a typed journal would be an easier thing to do.

This journal started as one or a few sentences per day, but then expanded into longer entries as the years passed. I kept it through my time as a lab tech at Michigan, on into graduate school at Stanford and then in my next life here in Berlin. My entries got much larger when the COVID-19 pandemic started, where I really started to question the state of the world and my place in it.

In the past year, my journal reached the one million word mark. That is roughly the length of the entire Harry Potter series.

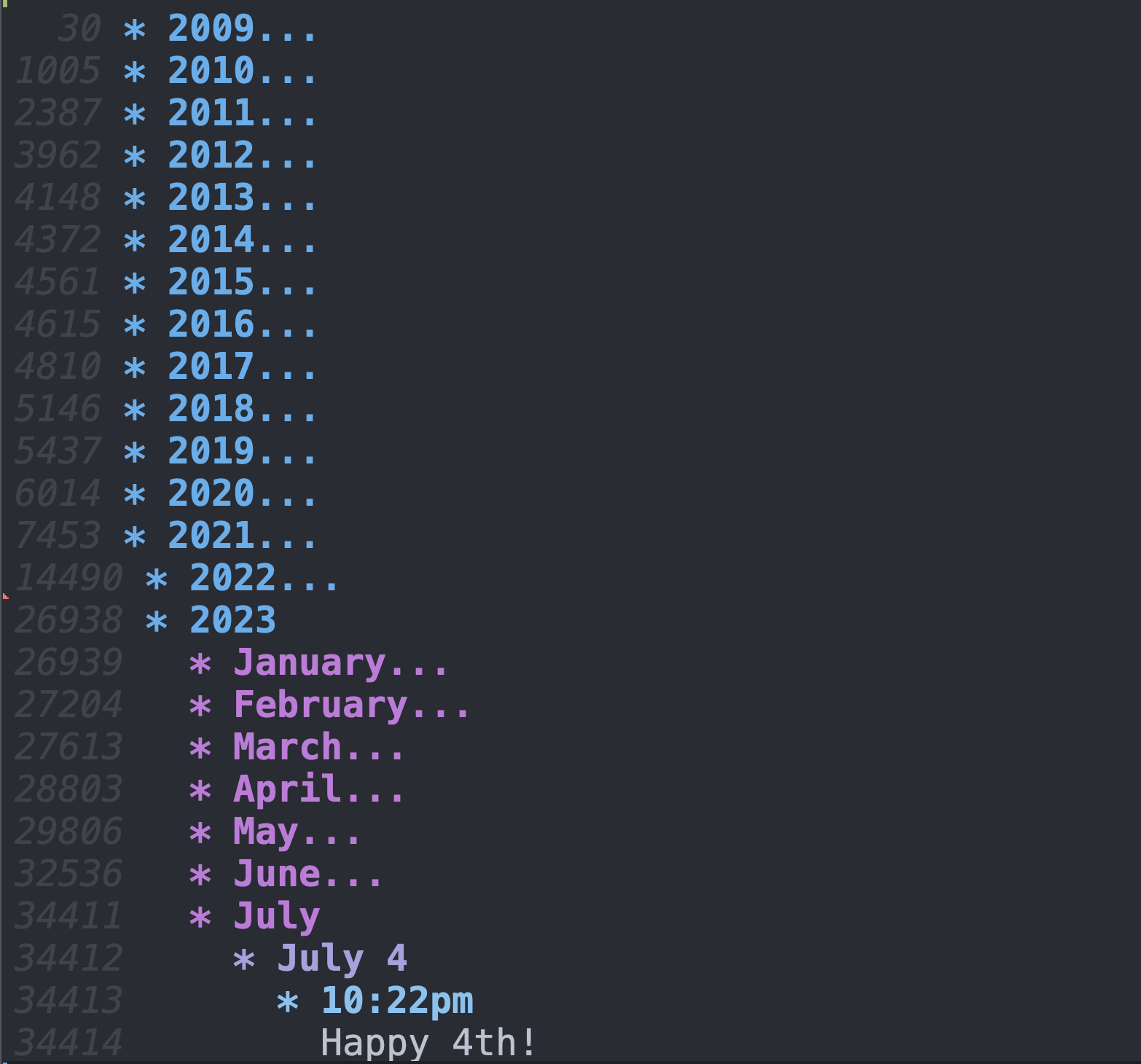

Here is the word count up through the beginning of December:

I am writing this essay at the end of 2023, where one of my projects is to review every journal entry from this past year. However, given the sheer number of words I wrote this year, doing so is no easy task. Thus, I re-purposed some of the AI-based tools I had developed in the past couple of years to help me.

This essay is a reflection of what one million words looks like, and what you can do with it. If you were to write one million words over the same length of time, what subjects would show up? What ideas would develop over that time. How would your memory of ten years ago compare to what was written? Are there things you completely forgot? Do you remember things as better or worse than they actually were? Did you have any predictions of the future that you can revisit (and were you right or wrong)?

In this essay, I will talk about my million word introspection, and I will also share the tools that I used to help me review these entries, which have use cases in any sort of note taking. My goal is to both inspire the reader to start a journal and/or double down on journaling, review it regularly, and to take a similar tool-based approach to help analyze their journal over time. Like investing, the benefits of keeping a journal compounds the longer you have it.

Anatomy of the journal

My journal was originally typed out in Microsoft Word. At some point, it got so bulky that even Word could not handle its size (it would take a long time to load all the pages so I could start writing). Furthermore, it was simply difficult to scroll through all of it, as it was expanding to hundreds of pages. Initially, I started breaking the document up into chunks with date ranges. Then, I discovered org mode.

Org mode is a major mode within the Emacs text editor (the latter has a bit of a cult following). If you have not seen org mode before, you can think of it as an older, less clicky, fully open source version of Notion. Org mode is therefore fully mine. Furthermore, the files double up as plain text files, as opposed to having a more complex and obscure format. This means that they will likely still be readable down the line.

But the reason why org mode is applicable to journaling is the use of collapsable bullet points. In other words, I can have a bullet point that is the year, another bullet point level that is month, another that is date, and another that is time. Then I can collapse all of it so we can only see year. Thus, I can jump to any entry anywhere at any time without scrolling through hundreds of pages. Here is a picture of what this looks like:

So you can see that I opened up to the July 4, 2023 entry from 10:22pm. The plain text shows up after time time-based bullet points. Then there is a keyboard shortcut (shift + tab) which closes everything up again so you're just back at the year. This is one million words, neatly organized, on a single page, and searchable.

All this being said, there are ways to add inline images to these journals. This is for another time, but if you're an org mode user, check out org-download. I often drop in hand-written stuff (either scanning pen and paper or using my iPad), or photos I took, or screen shots. In other words, it's one million words and then some. But again, this is for another time. This is just to say that there is a lot more you can do when you're using org mode as opposed to plain text, and if you're journaling, you want to capture as much of your life through as many mediums as possible. I've also uploaded little snippets of music I played on my piano, and voice recordings too. Whatever I can do to capture my subjective state in a way that my older self will be able to understand.

But anyway, back to the journal. What happens when you have written all this stuff? I can't just go back and read a million words from top to bottom every year. Or even the more than hundred thousand that I wrote in 2023. This is where you need help from natural language processing. I'll say right now that I'm not talking about chat bots. The use case here is to be able to go back and quickly see the relevant thing you wrote and when you wrote it, and to look for themes and throughlines. This requires a different approach.

Tools for exploration: mapper and nearest neighbor Search

Here, we're going to talk about the tools that I have used to review one million words of journaling. I'll give you the general structure here. If you're not interested in the technical details, then please skip to the next section where you'll be able to see the results.

Reading in the org mode file

In short, I read the org mode file line by line. I have the journal set up such that each paragraph is a single line, separated by an empty line, similar to the way I wrote this essay (which was also written in org mode). To get rid of the year/date/time lines, I exclude anything that starts with an asterisk (which is how you do a bullet point in org mode).

The year is preceeded by one asterisk (* 2023). The day is preceeded by three asterisks (*** July 4). Note that the "day" also contains the "month" information, so there is no need to include month (** July) in the code below. The time is preceeded by four asterisks (**** 10:22pm). Here is the relevant snippet:

# Function to read and process the org file def read_org_file(file_path): with open(file_path, 'r', encoding='utf-8') as file: content = file.readlines() year, day, time = None, None, None paragraphs = [] paragraph_details = [] # To store year, day, and time for line in content: line = line.strip() if line.startswith('**** '): time = line.strip('* ') elif line.startswith('*** '): day = line.strip('* ') elif line.startswith('* 20'): year = line.strip('* ') elif line and not line.isspace(): # Check if line is a non-empty paragraph paragraphs.append(line) paragraph_details.append({'year': year, 'day': day, 'time': time}) return paragraphs, paragraph_details

Create word embeddings

The word embeddings are created using the BERT language model. This has been around for a while, but it differs from the GPT-based models in a very important way. While the GPTs function as chatbots, BERT simply takes the strings (words/sentences/paragraphs) its given and embeds them into a high-dimensional vector space, where strings that are similar to each other in context will be physically nearer to each other in this vector space. In other words, the sentence "I played fetch with my dog" will in theory be located nearer to "I walked my dog" than "The clown rode the unicycle." The first two sentences involve things you do with your dog, so they're grouped together.

Specifically, the model I've been using is called all-mpnet-base-v2 from the sentence transformers python package. Once the paragraphs (lines) are extracted from the org mode file, you just have to feed it into this model for it to output the vector space. Because my journal is so large, it helps to have some code in there that saves the embeddings. I was saving them as csv files for the past year or so, but when I was refactoring, ChatGPT recommended the use of a .npy file, or numpy array specific file. I didn't know I could do that, so I went with it. Here is the code for the function, so you can see what it looks like:

from sentence_transformers import SentenceTransformer import numpy as np model = SentenceTransformer('all-mpnet-base-v2') def embed_paragraphs(paragraphs, embeddings_file='embeddings.npy'): # Check if embeddings file exists if os.path.exists(embeddings_file): print("Loading embeddings from file...") # Load embeddings embeddings = np.load(embeddings_file, allow_pickle=True) else: print("Embedding paragraphs...") # Compute embeddings embeddings = model.encode(paragraphs, show_progress_bar=True) # Save embeddings np.save(embeddings_file, embeddings) return embeddings

Reduce the embedding to 2 dimensions using UMAP

So now you have a two dimensional array of 768-dimensional vectors that correspond to each paragraph that you upladed. What happens now? Well, my PhD thesis was in high-dimensional single-cell analysis (CyTOF), which is a very visual field. We used nonlinear dimension reduction to visualize our outputs to quickly get a feel for what's there. If you want to see some of my work on that, go here. Anyway, as critical as I am about these tools (if you look at the previous link), I am still all for the narrow use case of quickly getting a feel for what's there. In the context of creating a map of journal entries, where each entry is a point, you can think of it as "thought space."

Here, we are using UMAP to achieve this end. Implementing this is simple in python, and its just a matter of feeding your vectors into the model. Each 768-dimensional vector now becomes a 2-dimensional vector (xy coordinates) when you can visualize on a simple biaxial plot. If two points are near each other in the 768-dimensional space, they will in theory be near each other in the 2-dimensional UMAP space.

The code for doing such a thing is below. Note that we're also saving the umap embeddings as a separate file, so we don't have to compute them over and over (which could very well produce different maps as well if we don't take care to set the seed). You'll also see that I'm using cosine distance. This is one of the standard metrics for dealing with high-dimensional space (as compared to Euclidean distance). If you want to experiment with different metrics, by all means do so. Here is some work I did to that end, to give you some motivation.

def compute_and_save_umap_embeddings(embeddings, umap_file='umap_embeddings.npy'): print("Applying UMAP...") umap_reducer = umap.UMAP(n_neighbors=15, n_components=2, min_dist=0.1, metric='cosine') umap_embeddings = umap_reducer.fit_transform(embeddings) np.save(umap_file, umap_embeddings) return umap_embeddings

Nearest neighbor searches

We also want to be able to do nearest neighbor searches on a given journal entry (or new text entrely) that allows us to see if we have written similar things in the past. This allows me to track ideas from their inception to the present moment. This work builds off of some previous work that I did here, involving nearest neighbor searches between new text and the Meditations by Marcus Aurelius (when I first started reading the Stoic texts a few years ago). This is in turn built off of my second publication, which remained a pre-print due to a combination of "reviewer number 3" and just being busy with moving to another country and starting my business. Anyway, my paper used k-nearest neighbors to analyze CyTOF data in many ways, while the rest of the field at the time was fixated on clustering.

Here, I'm taking a given text, and returning the k-nearest neighbor entries from the original 768-dimensional vector space. Why not from UMAP? Because when you compress high-dimensional space into two dimensions, you lose a lot of information, so you'll see inaccuracies between the orignal high-dimensional space and the UMAP space. To explicitly see this, have a look at my KNN Sleepwalk project (scroll to the bottom for a gif). Again, we are using cosine distance as our metric, just as we did with UMAP. The code for implementing a nearest neighbor search is below. In this example, we are setting the k to 10, but you can set it to whatever number you want.

from sklearn.metrics.pairwise import cosine_similarity import numpy as np def find_nearest_neighbors(query_embedding, all_embeddings, top_k=10): similarities = cosine_similarity(query_embedding, all_embeddings)[0] top_indices = np.argsort(similarities)[-top_k:][::-1] return top_indices

Web interface

In order to make these tools easy to use, I built web interface around them. I made two web interfaces. One for the map-based analysis and one for the nearest neighbor search. I did these both using the Plotly Dash framework. It was originally quite some work to figure out how everything tied together (here is a tutorial that I used), but now ChatGPT allows me to quickly change the UI/UX to fit my needs. Accordingly, I'll avoid the details here, but you can go the source code that I provide so you can see what the back end looks like. The next section will show you what the front end looks like as a side effect of the main point: the analysis.

Deep dives into the self

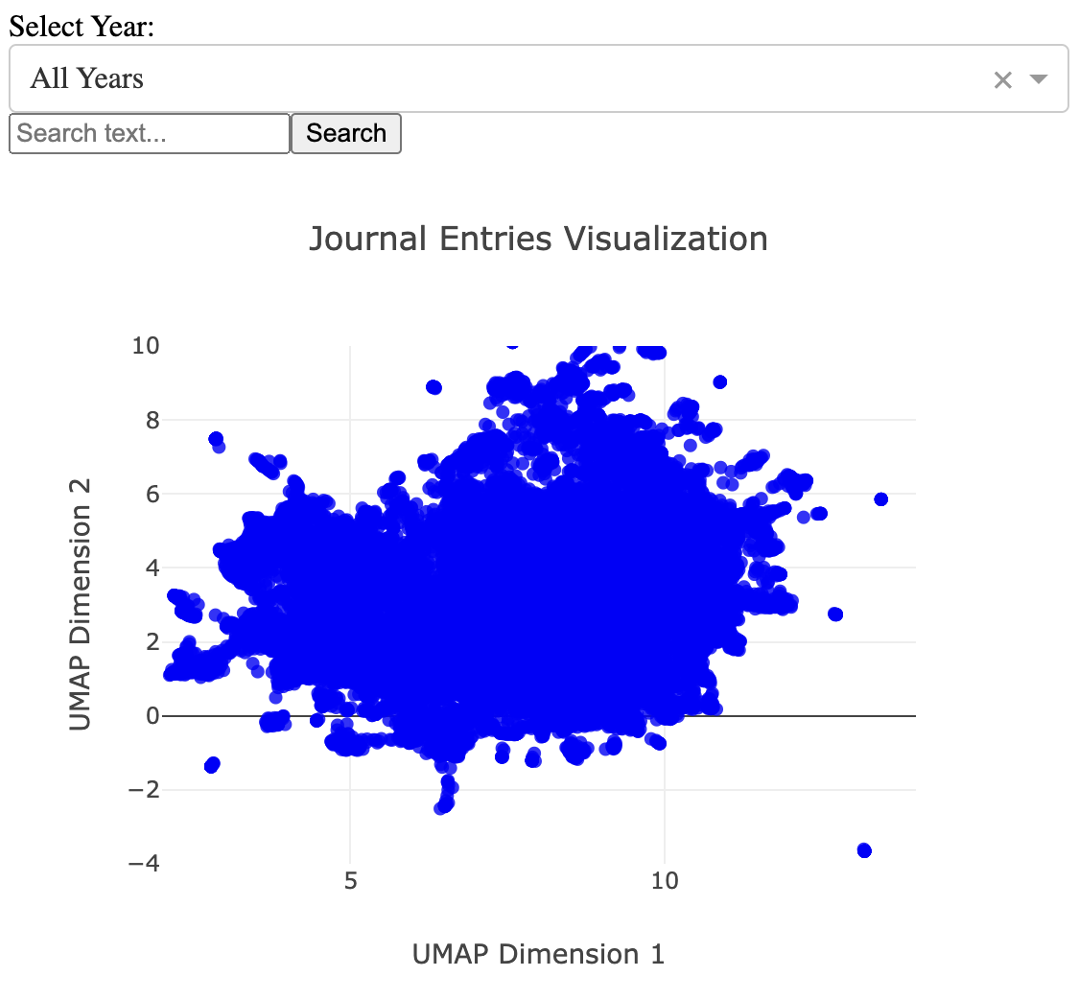

Thought space

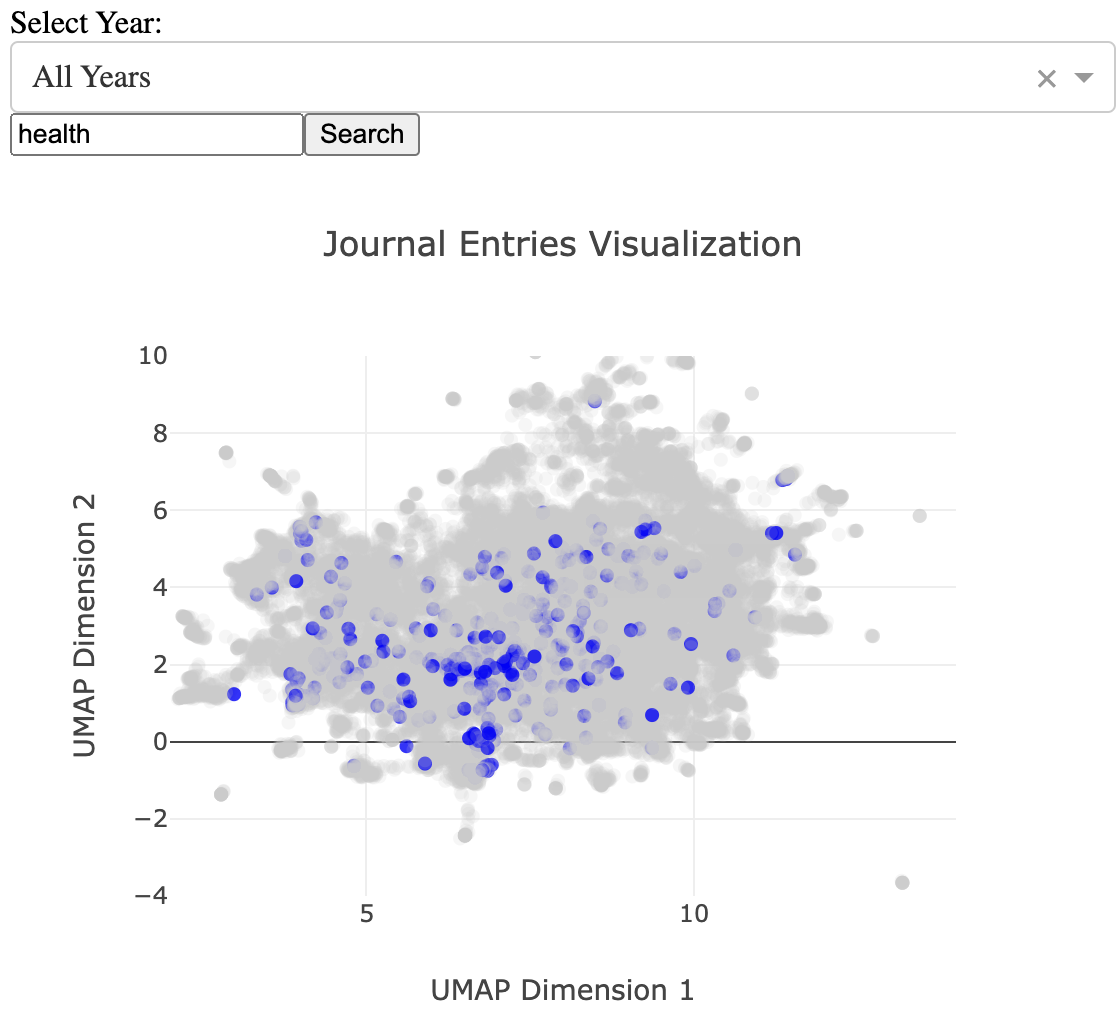

The transformed sentences compressed into a UMAP representation present an approximation of what I call thought space. I have a UI that allows for the querying of this thought space, in which paragraphs that are similar to each other in context will physically group near each other. The UI looks like this:

There is additional functionality that allows you to click on points and see what was written, as well as a dropdown as you can see, that allows you to select the years you want displayed on the map.

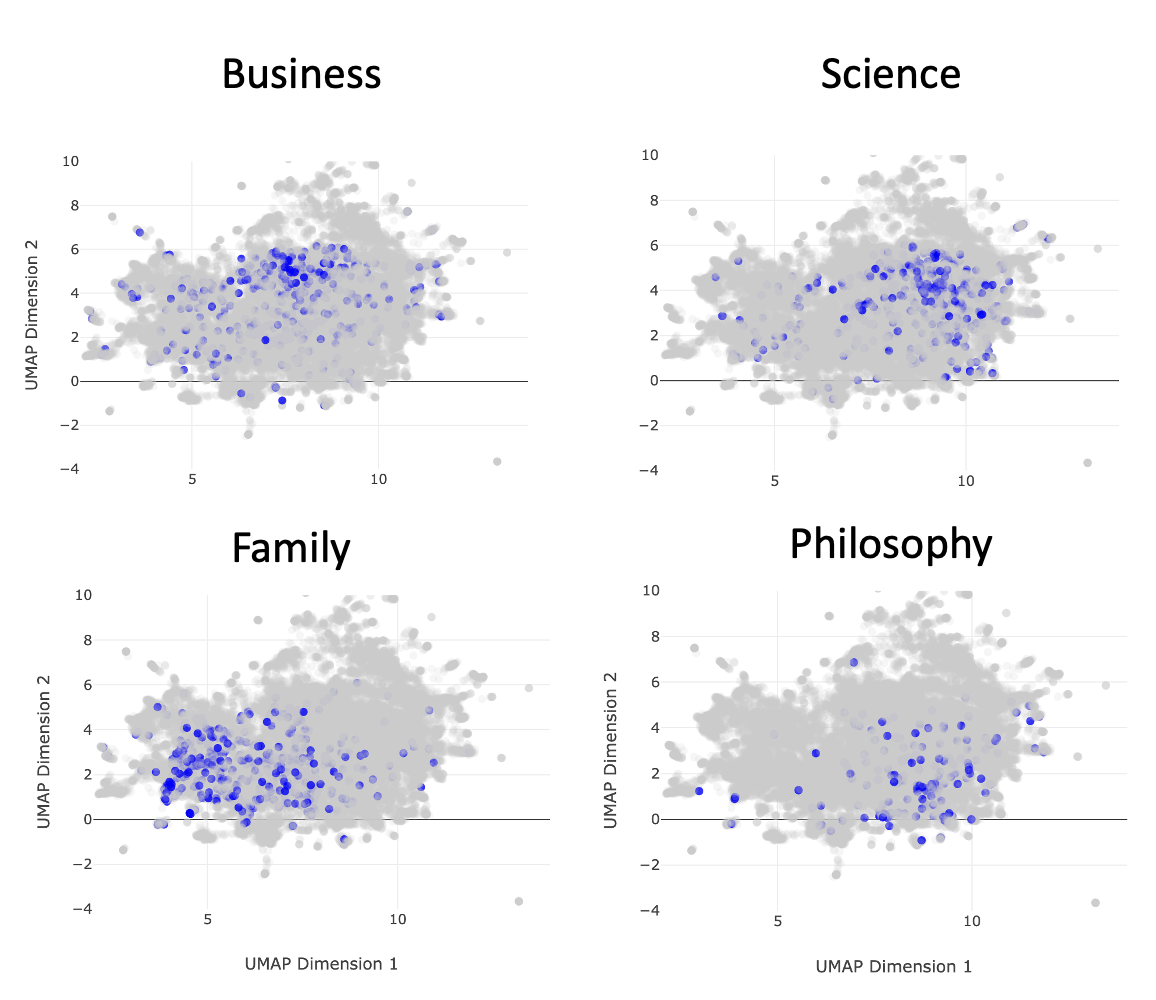

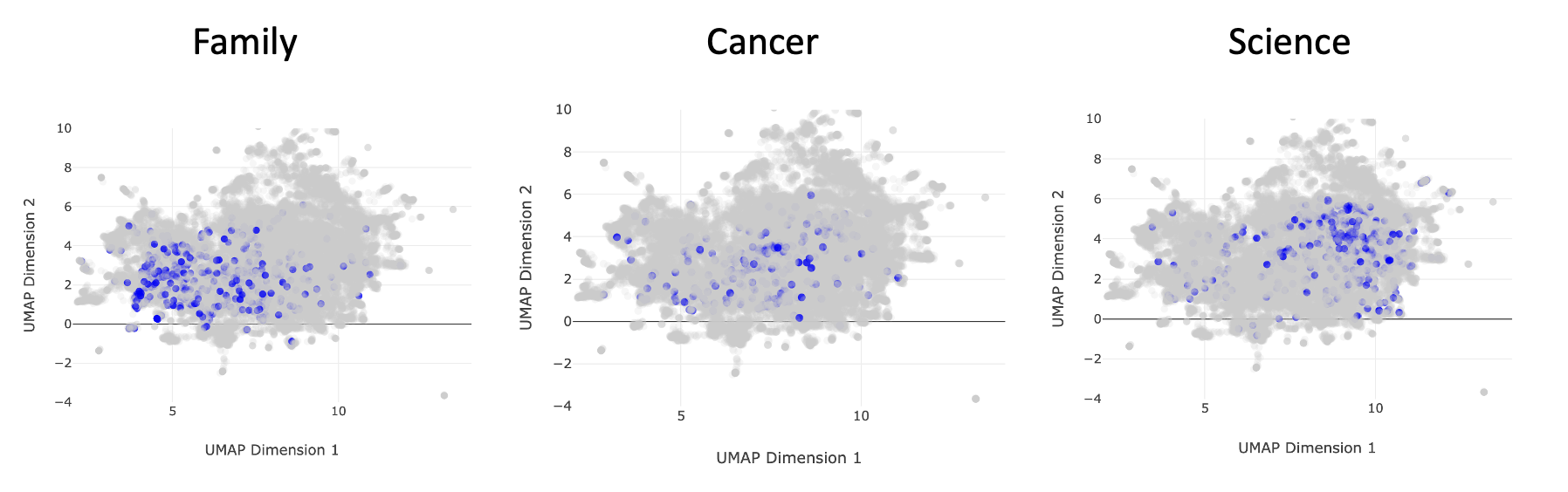

When I saw this map, which runs until the end of 2023, the big question on my mind what my journal entries in general are about? I can recall by memory the kinds of things I write, but my memory is not good enough for me to recall exactly what I was thinking about in November of 2014, or relevant to this analysis, how often I write about science versus family, and so on. The search bar in the UI allows for the map to be colored by any string of interest. Accordingly, I typed a number of things in, and I found a set of four words that appear to take up the majority of thought space: science, business, family, and philosophy. You can see this below:

I like how each of these subjects more or less occupies a particular swath of thought space. There are zoom-in capabilities limited only by the bounds of plotly that has allowed me to dig into each of these a bit more and see exactly what I was writing about and when. But most of that is a private thing. It's my journal afterall.

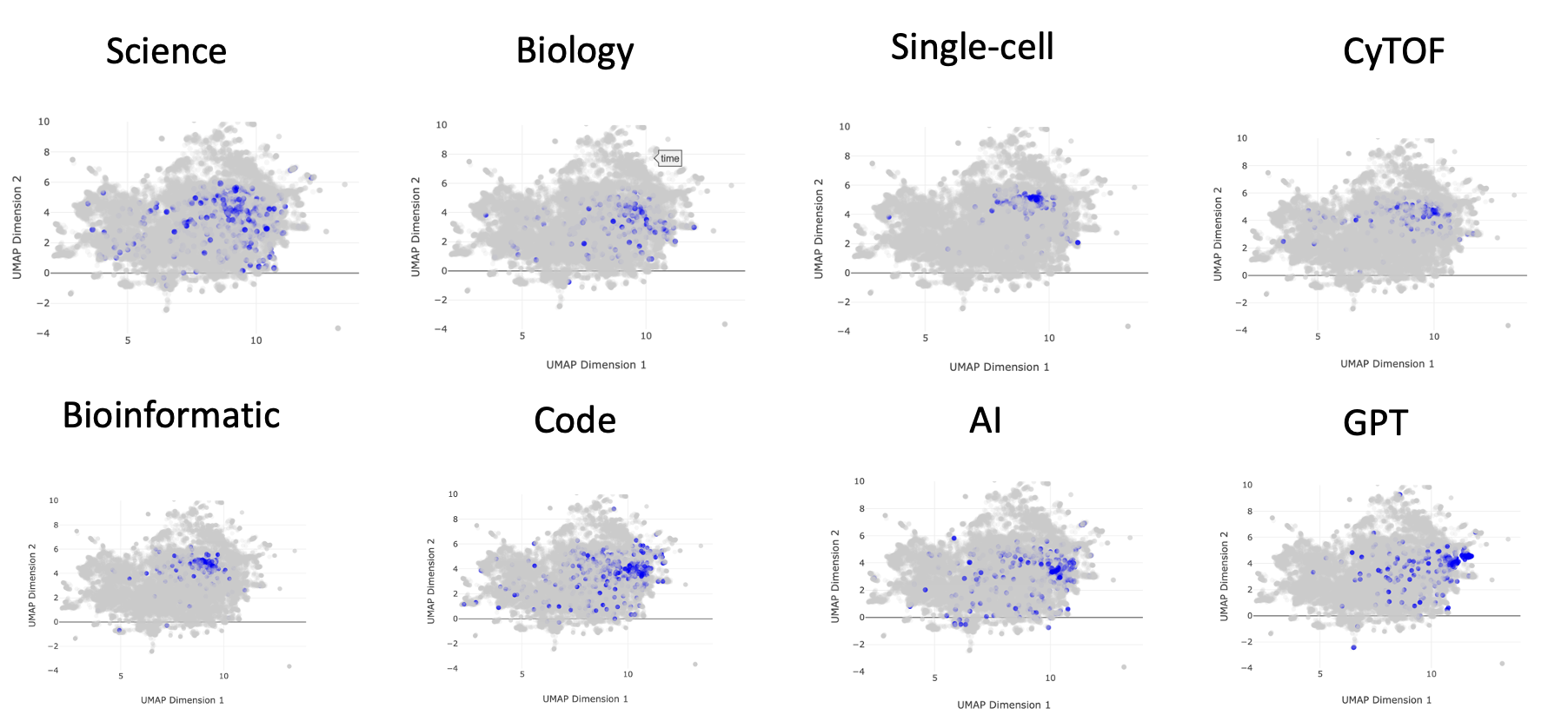

But for the sake of my readers, let's delve a bit into science, as it is a large amount of my public facing persona, and clearly a large swath of thought space. Let's use some additional keywords that I expect to be nestled in this science cluster, the content of my scientific inquiries. Eight key terms are presented below, with "science" being in the upper left as our positive control:

You can start to see subclusters within the "science" umbrella of thought space. One of these encompasses single-cell, CyTOF, and bioinformatic. This describes my PhD work with Garry Nolan, along with a large chunk of the work I do in my bioinformatic consulting business. You can also see a cluster farther to the right that encompasses code, AI, and GPT. This more technical cluster describes my journal entries around technical development that I in turn use to improve my data analysis work. Furthermore, more recent client work is in the domain of biosecurity, in which I research things like how AI will impact the ease of a malicious actor producing a pandemic-grade virus. Hence, I expect this cluster to grow relative to the others into 2024.

The last observation I'll note is that there are certain keywords that bridge the four major clusters that I originally characterized. For example, the word "cancer" seems to sit between the family cluster and the science cluster within thought space. This is likely because cancer has my scientific focus (my PhD was in cancer biology, and some of my client work is cancer-based projects), and is borne out of family tragedy. Hence, it exists somewhere in between the family and the science cluster. You can see this in the image below:

Mapping out thought space has turned out to be an elightening exercise made possible by advances in natural language processing and their availability as relatively easy-to-use python packages. There is a whole lot more I'm not showing because its my private journal, but I can assure you that this is a gift that keeps on giving.

For the external observer, I am comfortable letting the world know that a large majority of my brain's thought space, at least the fraction I write down in my private journal, encompasses these four domains: science, business, family, and philosophy. Let's see what this does to the tailored ads that show up on my feeds.

But those who know me well will know that I'm also obsessed with all things health and fitness. Where does that sit in thought space? The answer: everywhere. This is despite having a separate health/fitness log. The result for the keyword "health" is below. It appears to cover all four regions, though perhaps a bit less on the business region of thought space. This more or less makes sense. I was once a certified personal trainer, but at the moment, I am not interested in turning my sacred gym time into a job.

You've written about this before

In reviewing my entries, I have noticed that there are ideas that I think are new, but I find that I actually wrote about it in the past, sometimes years ago. I also find particular "moods" that I stumble into where I write a particular way about particular things. I want to be able to see these kinds of things in real time. This is where the nearest neighbor search comes in.

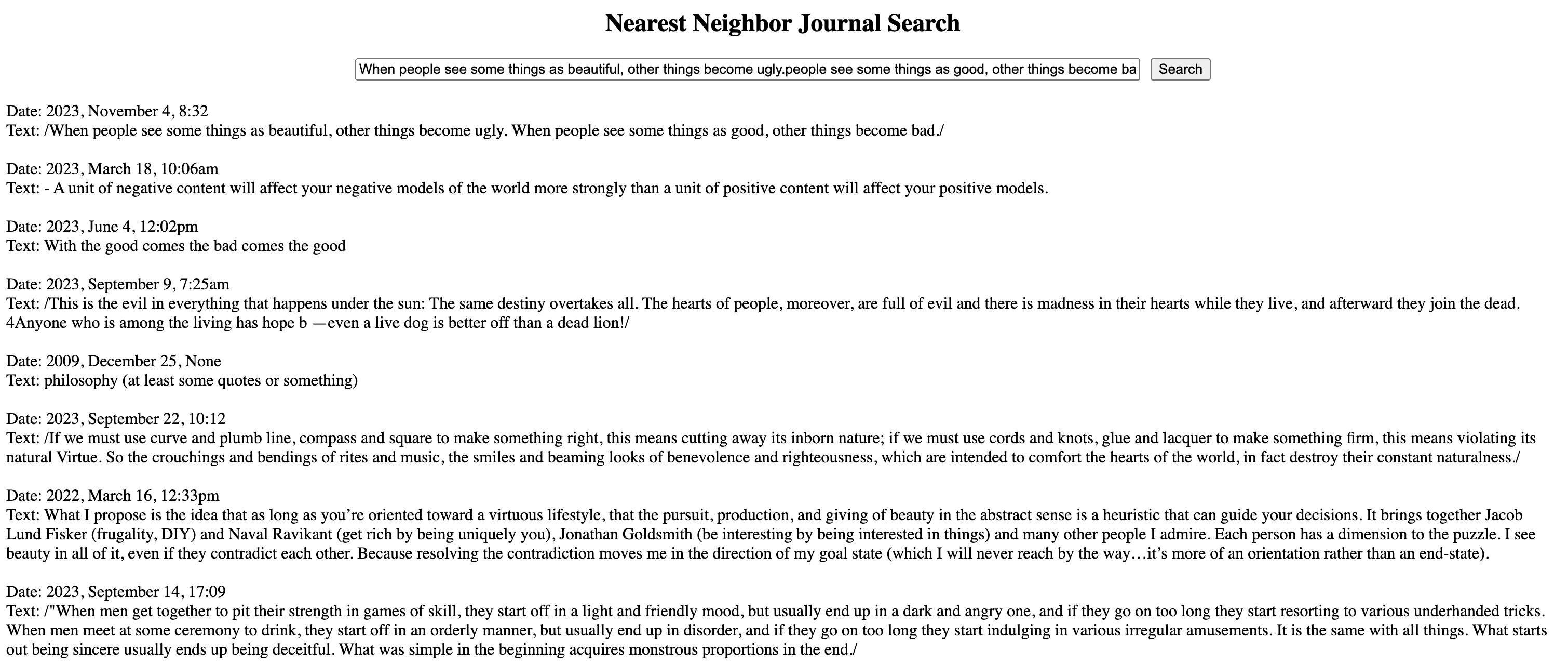

I'll show you what it looks like and what you can do with it. You start out with a basic search bar, and you enter something into it.

Given that we explored the science cluster in thought space in the previous section, let's explore the philosophy cluster here. A lot of my philosophical reading and writing centers on very old works, like the Stoic texts or the Taoist texts. Accordingly, we will start our inquiry with a passage from one of my favorite pieces of written material, the Tao Te Ching.

When people see some things as beautiful,

other things become ugly.

people see some things as good,

other things become bad.

Ok, place that into the search bar and we get (the text is small, so I'll explain what's there below the image):

The nearest thing is the exact quote, from November 4, 2023. The backslashes make it italic which is how I distinguish quotes in my journal. Then we have opposites: negative and positive, good and bad. From there, we have a typo-laden quote from September 9, 2023. What's that from? Ecclesiastes 9:3 and 9:4. Perhaps its a combination of the "evil" them, and the oppostes talk between live dog and dead lion. Then we have a weird one that is mainly the word "philosophy." So it seems like the model directly picks up that we're in some sort of philosophy space. Then we have the "if we must use curve and plumb line…" quote. This is from Zhuangzi, chapter 8, a Taoist text. The quote at the bottom is also from Zhuangzi, chapter 4.

So interestingly, this 10 paragraph neighborhood contains quotes from Taoist books the Tao Te Ching (the center) and Zhuangzi, but also the book of Ecclesiastes from the Old Testament of the Bible. I am going to guess that it is a combination of the coincidence of opposites as well as the topic of good and evil (or good and bad, as in the original quote). Anyway, one thing I like to do is pick a quote from a wisdom/philosophy text and riff on it. I am guessing that this makes up a good chunk of the wisdom cluster: quotes and quote-riffs.

Note that the same way you can go down rabbit holes on YouTube by simply clicking the recommended videos over and over, you can do similar things here by taking any search result you find interesting and placing that into the search bar and running it again. This allows you to find relevant regions of thought space (and interesting regions you simply haven't explored yet) very efficiently. I'll note that I did that just now with the above results and ended up in an existential risk / end of the world rabbit hole. I have seen similar philosophy -> doomsday discussion patterns play out on the internet before. Hmmm.

Conclusions

Journaling is good

The most important thing that I want to convey in this article is that keeping a journal for a long time is a very good thing to do. Aside from the benefits of daily journaling, it makes it easier to live an examined life. It is very interesting, and very fun to look at where I was at a decade ago, both in terms of what I was up to, and what I was feeling at the time. There are often contrasts between what I remember and what I actually wrote down. I anticipate that this will continue to become more interesting, beneficial, and fun as time goes by and my journal continues to grow.

The use of plain text and the use of org mode in particular has made it much easier to have and maintain such a large journal. I can collapse a million words into a nicely laid out series of bullet points that correspond to year, date, and time. I can go to any time period with a couple of clicks, and search the entire document for keywords. With the size of the joural now, my natural language processing tools are helping me dive into it.

An automated Zettelkasten

At the time of writing there are tools that are making a particular type of linked note taking popular. This is known as the Zettelkasten (German for slip box) style of note taking. The easiest way to understand what this is would be to browse Obsidian's note taking system. You take notes and you link them until you have a personal wiki that you can either click through (like hyperlinks on Wikipedia) or view the entire network.

I have tried this before in org mode with a tool called org-roam and it just didn't stick. You end up with a ton of little one-page notes and you have to go through and link them to each other yourself based on what you think is relevant. I just didn't have the motivation to put that much work into my notes. But I did want to be able to "link" the contents of my journal somehow and be able to visualize it.

Thus, the use of BERT embeddings was able to turn the contents of my journal into so-called thought space, grouping similar paragraphs physically near each other. From there, I had the ability to either view thought space as a searchable interactive map that I could browse, or to view my journal in terms of nearest neighbors to any piece of text I input into a search bar. The latter with the recursive "put the result in the search bar" method that I was talking about allowed for the equivalent of the "clicking through" that you'd otherwise get with a Zettelkasten tool like Obsidian.

Of course, the use case that I'm talking about here is my journal. However, if this is indeed more like an automated Zettelkasten, then there are use cases that go well beyond the simple act of analyzing a journal.

Who am I?

I am assuming that everyone asks the question "who am I" from time to time. This is a particularly difficult question, as the passage of life makes the self concept rather dynamic. However, a million words of written journal over 15 years can start to get at this question a little bit. Looking each paragraph of my journal entries in a map form, thought space, and later interrogation of what was written in each region of thought space, allowed me to test my self concept against what I actually have been writing down over the years. Doing such a thing only really works if your journal entries are faily unfiltered. Doing this on your social media posts probably will not provide very much insight into who you actually are, though it may offer utility when coloring it by engagement metrics.

Not shown in this article is the ability to look at how thought space changes over the years. The content of my journal entries from 2010 is quite a bit different from the content of my journal entries now. One can get a bird's eye view of this by comparing thought space from 2010 and 2020, for example.

So who am I? My tech-enabled journal review suggests that I am a lot of things. There is a concept in cognitive science around just this known as the dialogical self, that makes sense in the light of revealing my journal entries. It's the idea that the self is actually a lot of sub-selves (based both on internal self-concepts and external roles) in "dialgogue" with each other, that leads to your actions. The best way to grok this idea is to watch the movie Inside Out. Or at least watch the trailer. Anyway, lots of different versions of me have written into this journal, and I am not just one thing. It's kinda refreshing to realize that, really.

Additional use cases and future directions

I take a lot of notes on the computer. I used to keep everything in Evernote, but now I'm keeping everything in org mode files that are orgnized in a way that is similar to my journal: by year/date/time. I use tags if I want to drill into particular subjects, but otherwise I can use the same software to organize things automatically.

One place I'm limited at the moment is that, as I have said before, my journal (and the rest of the notes I take) have many different modalities of information: typed, hand-drawn pictures, screen shots, handwritten notes, voice memos, music, etc. The BERT embeddings work only for the typed text at the moment. So far as I'm aware, there are tools that allow for the conversion of handwritten notes to typed text. The same goes for sound recordings. I have yet to add this, in terms of producing the data that get embedded. Even if I do have this, there are still pictures and diagrams that are otherwise difficult to put into words, though perhaps down the line I'll figure out how to include them into a multi-modal embedding.

Either way, I have been iterating on this concept for a few years now, and it's finally at a point where it's really starting to pay off in terms of staying on top of all of my writing. I can imagine similar tools benefiting writers, researchers, and students down the line. Until Obsidian and whoever else adapts this into their system, I'm going to leave the software publically available here for anyone who wants to do this on any of their stuff.

Happy journaling!