How I transitioned from biologist to biology-leveraged bioinformatician

I can’t be as confident about computer science as I can about biology. Biology easily has 500 years of exciting problems to work on. It’s at that level.

Donald E. Knuth. Computer Literacy Bookshops interview, 1993

Introduction

This article is written for biologists and research team directors with a biology background. If you are a bioinformatician, then perhaps you can be entertained by my perspective, here. Everyone has a slightly or massively different path, afterall.

The purpose of this article is to give you a foundation of what it is like to go from thinking like a biologist to thinking like a bioinformatician (or computational biologist, or data scientist). I do this by summarizing my journey from biologist to biology-leveraged bioinformatician, introducing basic concepts that were real "aha!" moments along the way. Since this transition, I have been able to provide bioinformatics-based services on a self-employed basis, dating back to 2016. Hopefully in reading this, you will see that you can do this too.

For an audio version of my journey from biologist to bioinformatician, plus some added goodies about my path to self employment, please listen to my guest appearance on the Developer Stories podcast, part 1 and part 2.

Learning how to code

I had two attempts at learning how to code. The first was a genomics class in 2012, done in Perl. The class was too much too fast. I had to learn the basics of genomics (it wasn't my background), I had to learn how to code, and I had to learn how to analyze genomics datasets. The whole thing was a big blur of cortisol. So I'm not going to talk about it except for here, only to say that if you've had a similar experience, know that you might have simply been in the wrong environment.

My second attempt was in 2015, when I took Stanford's CS106A class along with the undergrads (I was 28). This was a completely different experience. One thing that helped was I started studying the material about a month prior to the class starting, so I could start ahead rather than falling behind. Another thing that helped was that the class was much more focused. I just had to learn how to code, and that's it.

Karel the Robot

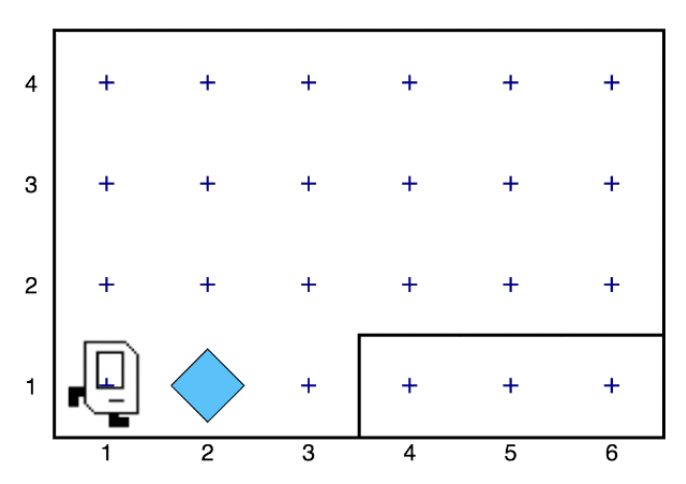

We started with Karel the Robot, available to the public here. It's such a simple concept, but was surprisingly deep in terms of just how much it taught me, and how much confidence it gave me. Let me try to distill some of the magic here. Have a look at the image below, so you can get a feel for what Karel is.

We have a robot facing east. In front of him is a beeper. He runs in python. Your python code consists of commands. The built-in ones are move, pickbeeper (pick up the blue diamond), and putbeeper, and turnleft. So if you have code (taken from here) that looks like this:

from karel.stanfordkarel import * def main(): move() pick_beeper() move()

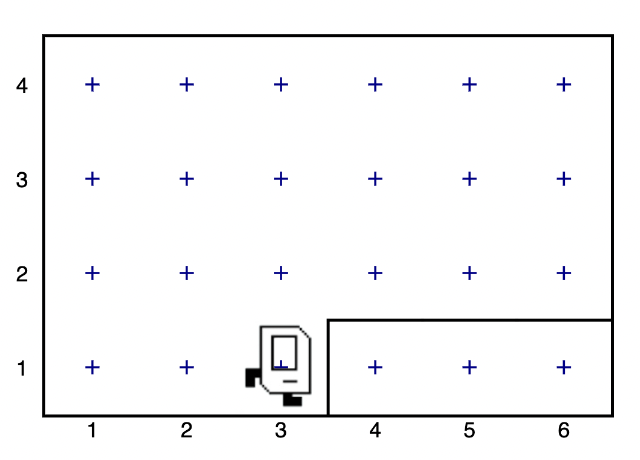

Then Karel ends up here:

The beeper is gone because Karel has it now. He moved twice, so he is two spaces to the right. That line is a wall.

And that was coding! You gave Karel a set of instructions, written in a particular syntax, that allowed the computer to interpret the language, which got Karel to do the things. Alright, let's do some more of that.

Functions

Ok, here is where it gets interesting. We're going to look at functions, which one can think of as a fundamental unit of innovation. Suppose Karel wants to walk along that wall, and end up at xy position (4, 2). What does he have to do?

- Turn left.

- Move.

- Turn right.

- Move.

But we have a problem. Karel only knows how to turn left. So to make Karel turn right, we have to write turnleft three times. So we end up writing the following:

from karel.stanfordkarel import * def main(): turn_left() move() turn_left() turn_left() turn_left() move()

And maybe that's a bit more unsightly and inconvenient than we wanted. So it's time to innovate. We're going to make a function that teaches Karel how to turn right. Then we can use it over and over again forever, as long as it's written in.

from karel.stanfordkarel import * def turn_right(): turn_left() turn_left() turn_left() def main(): turn_left() move() turn_right() move()

And this brings me to my big point. You've heard of the phrase "we're standing on the shoulders of giants." This is it. People who use our code above will be standing on our shoulders. The shoulders of the highly innovative creation of the function turn_right. For every invocation, we use one command instead of three. You can turn anything into a function. Any number of commands that do a thing that you want, that you anticipate doing more than twice. You turn it into a function. This is a huge part of learning how to code, and learning what programming actually is.

Final point: you'll hear the phrase "don't reinvent the wheel" throughout your journey. While this does matter when you're providing timely bioinformatics services for clients, I take the opposite approach when I'm innovating. I literally reinvent the wheel, or at least stop caring about whether I'm doing so. If I reinvent a wheel, it's probably going to be a bit different than the existing ones. Maybe in a way that serves as a contribution to the field. I have seen this happen many times in my thesis lab, one of the most innovative environments (if not the most) I have ever been in. To read more about that, please go here.

Problem decomposition

Another key concept embedded in here is problem decomposition. This is the idea that when you're dealing with a complex problem, you break it down into pieces. Here, we were initially using high-level abstractions like turning right, prior to even thinking about how we're going to implement turn_right in python. Perhaps thinking about how we're going to implement turn_right would make us nervous because it's just too much to think about. Problems are hard. Even today, I will get overwhelmed if I don't properly decompose these problems prior to attacking.

Any biologist understands problem decomposition when thinking about complex experimental design, where this is no shortage of controls, replicates, confounds, late night time points, pre-made buffers, and the like to consider before the experiment begins. Any director understands problem decomposition in terms of the MECE trees that McKinsey teaches you.

A variant of problem decomposition is something I use quite a bit, and something Claude Shannon used quite a bit: solve a simpler but related problem. If the problem I'm facing is overwhelming to the point where I don't even know how to decompose it, I just simplify and find a little corner of the problem domain that I can start working on, even if it's not the same problem but a related one. This at least gets the psychological momentum going, which moves me into the flow state, which eventually moves me right into the core of the problem. I write extensively about this, and especially the flow state, here.

Loops

Ok, now let's introduce one more concept. Loops.

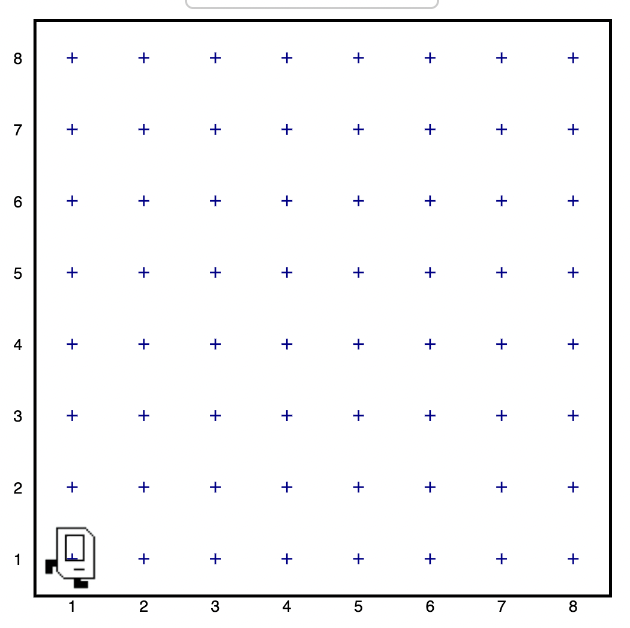

Let's suppose you have Karel in the following 8x8 grid:

Ok. Let's say we want Karel to move across the grid from one side to the other. How would we do that? We would have to type move() 7 times.

from karel.stanfordkarel import * def main(): move() move() move() move() move() move() move()

Ok, that was a bit convenient, but we got through it. But wait. What if the grid were a million by a million, and Karel had to get all the way across. That's typing move() 999,999 times. And we're busy. Who has the time for that? What if there was a way we could create some sort of loop that would tell Karel to move 999,999 times?

Well…

from karel.stanfordkarel import * def main(): for i in range(999999): move()

Done. We just saved ourselves quite a lot of time. If you know what you're doing, between loops and functions, you can make code that runs very efficiently, and save people a lot of time. A lot of what I do in bioinformatics involves getting things done fast. That means having a good menu of relevant functions that I wrote, and using loops liberally, given that a lot of my data involves iterating across matrices that can be millions of rows or columns.

But it goes without saying that a lot of computing is iterating (looping). Video games operate in a so-called game loop. Processes from cellular automata to turing machines are loops executing a specific rule set. Vector and matrix operations are often iterators, which can take the form of loops, or higher level functions that are loops under the hood. And zooming all the way out now, philosophers like Joscha Bach, who interpret the universe as a discrete process, think of it as a loop over very small time increments, where basic rules are followed among subatomic particles iterating through space.

Ok, I'll stop here, as going further is beside the point (as much as I'd enjoy doing so). What matters is you're giving the computer a menu of instructions. The computer will inerpret what you do literally. When things are inconvenient, you create new functions or use things like loops to allow fewer lines of code to do more things.

I encourage you to play around with Karel the Robot. I did so for 3 weeks in CS106A, and I had the foundation to get through the rest of the class without hitting any fundamental road blocks. Because all the building blocks were there for me to build off of. It was a huge time commitment, but it was more than doable. It was immensely enjoyable and empowering. It's hard to describe the feeling of being able to literaly program anything you want on the computer, and having the confidence that you could learn whatever you don't know, to get the thing done. The digital world becomes your oyster.

On languages

I remember having the misconception that after learning my first programming language, the next one would be just as hard and take just as long. This is not true. When you learn python, learning R will simply be a matter of learning the syntax and learning the specific quirks of the language itself. This is because within python, and within Karel, you will have learned many of the core concepts in computer science. These concepts are used in every language, in higher and lower level abstractions. It will be work to learn a new programming language, but it won't be like learning German after learning Spanish (I speak from literal experience).

The next section, on mass cytometry analysis, initially involved MATLAB, and then moved more toward R. But if you know python, you'd be able to at least read the code and get what's going on. And on that note: please write code as if others are going to read it when you're not there. This will save many people headache down the line, including future version of yourself reading code you wrote however many years ago

Mass cytometry and the first principles of bioinformatics

Let's talk about mass cytometry, also known as CyTOF. This was a tool developed in the late 2000s by Scott Tanner at University of Toronto, but whose potential was fully realized by Garry Nolan, my thesis advisor. The landmark mass cytometry for immunology paper came out in 2011, and I joined the lab in 2012. The technology was still new, and there were no best practices for analyzing this type of data in biology aside from those developed by the lab and its collaborators.

What does this feel like? It felt like the world was our oyster. Whatever it is, try it! Imagine that all the stuff you do with Karel the Robot above is completely new, and you're one of the few people in the world who have played around with Karel the Robot, and all the stuff you do with Karel is highly relevant to BioPharma. What would you do in such an environment?

Try things!

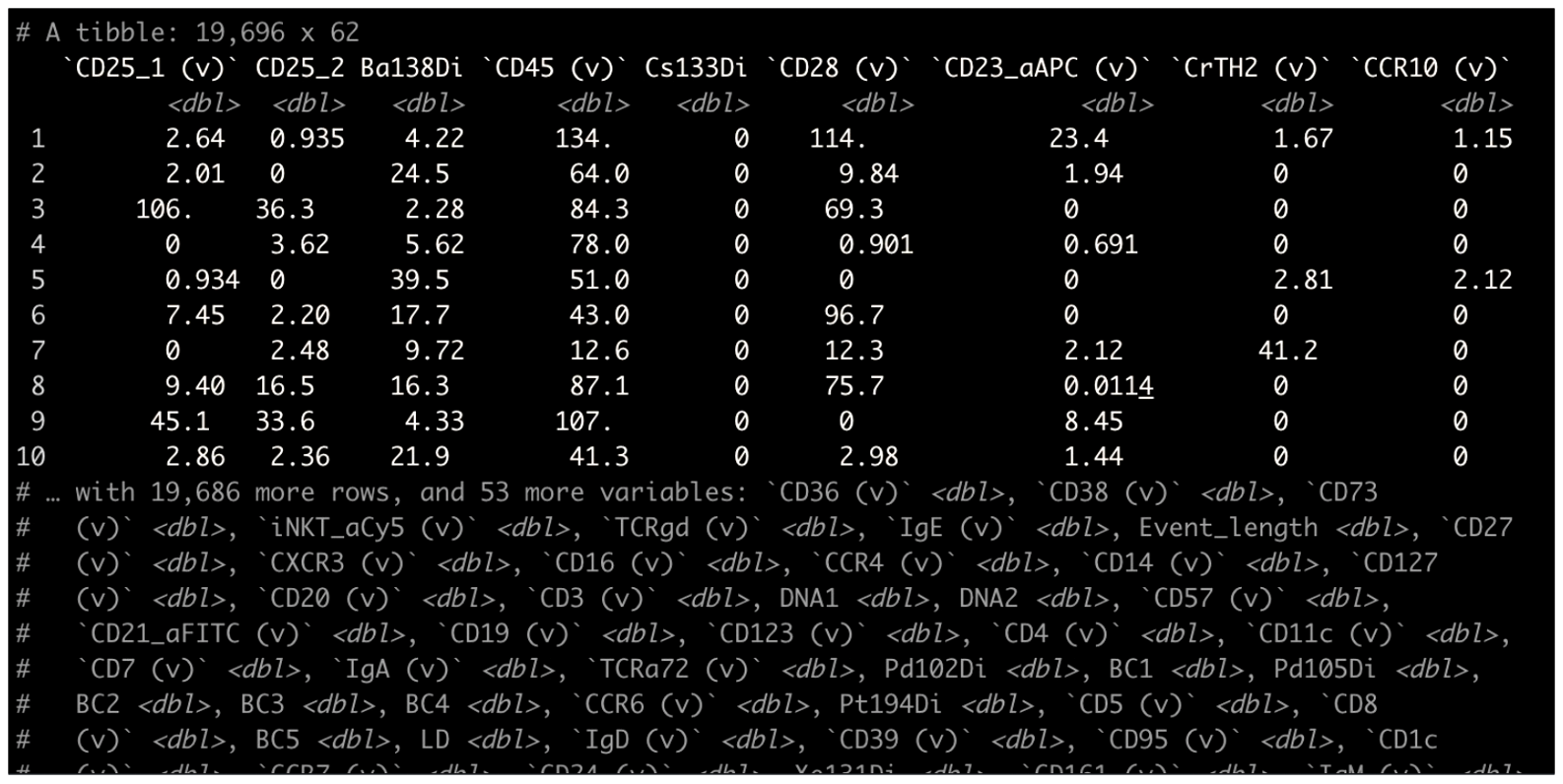

Unlike single-cell sequencing frameworks like Seurat, we were dealing with the raw data matrices. A typical CyTOF dataset was not a high-level object. It looked something like this:

Somehow, this had to get converted into something that was human-readable. One of the critical aspects of CyTOF analysis back then, that still shows now, is that it was highly visual. Why? One reason is because data visualization allows bioinformaticians and biologists to properly communicate, and for scientists to properly communicate with non-scientists. Another reason is visualizing everything provides plenty of opportunity to run sanity checks. Does the output make sense?

Biologists, this is where you will shine. CyTOF then and now, along with single-cell sequencing and high-dimensional imaging datasets that are taking off now, require the eyes of people who know biology deeply. Let me show you what I mean.

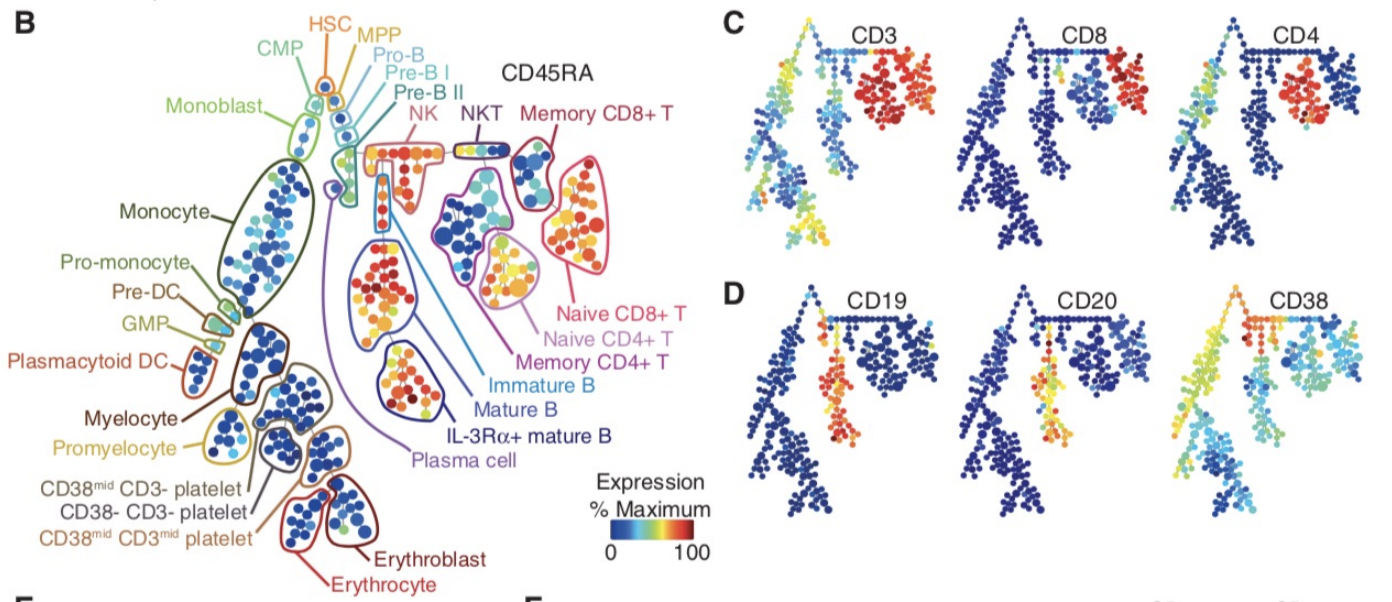

If we roll the clock back to 2011, one of the images that arguably sold the immunology community on the utility of CyTOF was this:

Ok, let's unpack what this is. This is mouse bone marrow data run through what is called SPADE, and it's from this paper, from a collaboration between the labs of Garry Nolan and Sylvia Plevritis (one of my thesis committee members and an awesome person).

The spots you're seeing are so-called "clusters." These are clumps of cells that are grouped together. Then these clusters are strung together algorithmically into what's called a minimum spanning tree. Ok, but putting our biology hats on, what we see is a classic hematopoietic tree. But this data was constructed algorithmically, using CyTOF bone marrow data as input. There was no biologist building the tree.

In other words, the right algorithm applied to the right data from the right technology was able to recapitulate decades of research in a single go. Contrary to popular belief, Garry Nolan didn't "invent" the CyTOF. Rather, he had the acumen to see that such a technology and the proper data analysis would be able to have such an impact on the immunology community. This was borne, at least in part, out of having both a deep immunology background and a deep bioinformatics background, along with the drive to take action. In other words, I think you can develop this acumen too, and this is a large part of my motivation to write this article for all of you.

Acumen and all, you can imagine what was going through the minds of the immunologists at the major cytometry conference CYTO 2012 in Leipzig, Germany (I was in the audience) when Garry, the keynote speaker, was showing these images to a packed audience. What will this reveal about immunological diseases? Cancer? What will it show with my stuff? The future was full of possibility[1].

Again, it was so new that literally you could do anything with it, and it would be new. On the bioinformatics side, there were no R and python CyTOF libraries or any of that. Just the bioinformaticians (I wasn't one yet), working closely with the biologists (me at the time). If you're ok with this, it's exciting. If you're used to high-level frameworks and well-established best practices, this can be stressful. I enjoy this type of work, so if I go to an environemnt where people don't enjoy this type of work, then I can get paid to do what I love.

Why am I lingering so much on this? Because when you're using modern frameworks like Seurat, or some of the new CyTOF frameworks like diffcyt or SPECTRE, I would encorage you to peel as much of it back as possible and play around with the innards. If you do it like this, weird bugs that come from lower levels of abstraction won't bother you so much. I can't imagine learning bioinformatics at the depth I did without having one that.

Want an example? Consider my version of the PBMC 3k vignette from Seurat. In there, I go through many of the major commands, and try to build each one up myself. Want an example of bioinformatics done without any major frameworks? Have a look at this CyTOF analysis vignette I wrote. What happens when you operate closer to the metal for long enough? You find hacks that can take you in a new direction. Have a look at how I tricked Seurat to analyze CyTOF data.

What's my point here? Try to operate from first principles as much as you can. Even if you're using high-level abstractions, understand what's going on under the hood. This will slow you down intially, but will greatly benefit you down the line. There are all kinds of issues you run into when you encounter "real world" data, that will rely on how well you understand the fundamental concepts. Furthermore, you will have to rely on first principles if you are analyzing data from any new methods that are being developed or utilized in your research.

What if you're a biologist who is not going to go deep into the weeds? Understand the concepts at a level where you can get some intuition. One example is a LinkedIn post that I made a while back, where I warn biologists and research team leaders to watch out for single-cell sequencing data that hasn't been integrated. I made this post after I came across this exact thing with one of my clients. They didn't see it, and their collaborators didn't see it. And the reviewers of the paper didn't see it. This led me to understand what is really needed here: intuition.

Bioinformaticians, biologists, and research team leaders need to be able to look at an analyzed dataset and say "no…that doesn't look right." How do you get to the level where you have a spidey-sense around bioinformatics? Again, by understanding your corner of biology, bioinformatics, and their relationship as deep as you can.

Summary and conclusions

To learn bioinformatics, you have to learn the basics of code. Luckily, programs like Karel the Robot can teach you the core concepts in a matter of weeks. A basic class like Stanford's CS106A will give you this and more. You can find old lectures on YouTube that are perfectly relevant today (though they are in Java, the core concepts are the same). If you don't plan to actually code, you should at least learn it to the point where you can run scripts if you're a biologist, or effectively communicate to comp bio teams if you're a biologist or a research team leader.

To learn bioinformatics, you need to understand whatever you're doing as close to first principles as possible. You might be working with a sophisticated framework where you don't need to deal with the innards of whatever it is. If that's the case, I am arguing here that it would still help to understand as much of what's going on there as possible, even if it initially slows you down.

Finally, I'm betting that your strong biology background, your understanding of computer science, and your understanding of bioinformatic tools, and your ability to effectively communicate with bioinformaticians will give you a gut instinct that few actually have. A gut instinct that could very well save you and your team from all kinds of issues down the line, and lead to both high quality science and groundbreaking innovations. Remember, I've seen this first hand.

Best of luck!

Footnotes:

[1] I remember feeling like the cures for cancer and major immunological diseases were right around the corner. But of course, it's more than ten years out and we have a long way to go. Why? Because with every new innovation (high-dimensional imaging is all the rage at the time of writing), we remember that biology is complicated.